Brotkrümelnavigation:

Hauptinhalt:

Anthropocene

Inquiry-based learning topic “Water”

Claudia Mewald

Young children are already able to understand their experiences in the biological, physical, and psychological world. They create implicit explanations for events or developments like adults, but they cannot yet add their own experience or deduct conclusions. If they are given the opportunity to learn through active inquiry, scaffolded language development, and collaboration in pretend play and educational games, children will create their own explanatory systems. In inquiry-based learning, children are free to be curious, ask their questions about the world around them, and find answers followed by new questions. Thus, learning designs about water, following an inquiry-based approach, should include activities that encourage children to &nb

Water: first words and concepts from the concrete domain

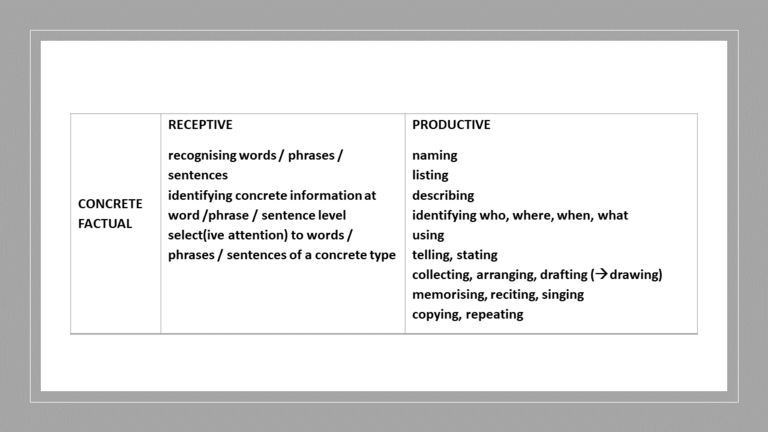

Even very young learners know what water is: They have been drinking water, playing with it, and using it daily for hygiene. Reflecting on the availability of water, exploring the sources of water, and the forms it takes, are parts of the concrete exploration of water. Pupils use concrete-factual thinking if they work at word, phrase or sentence level, identifying, matching, naming, telling, reciting … simple texts about water (see Table 1 in the left margin).

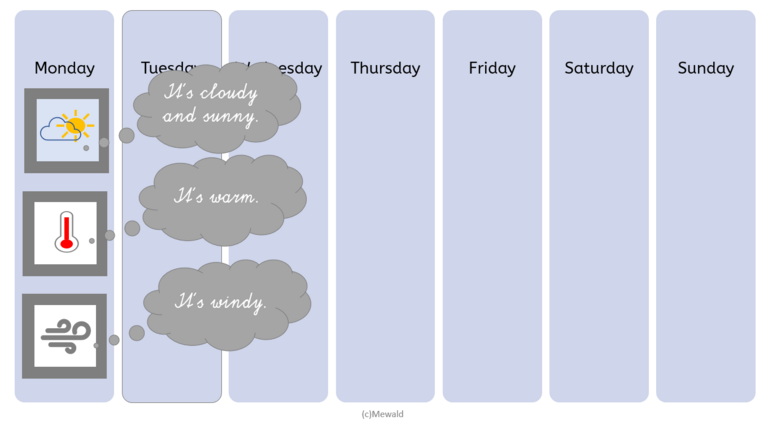

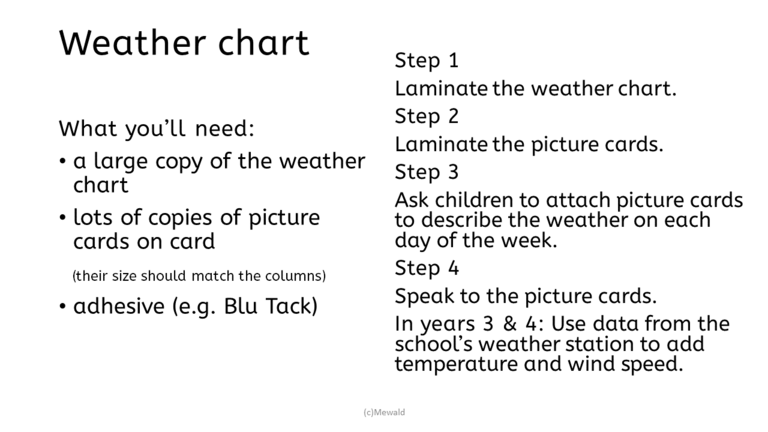

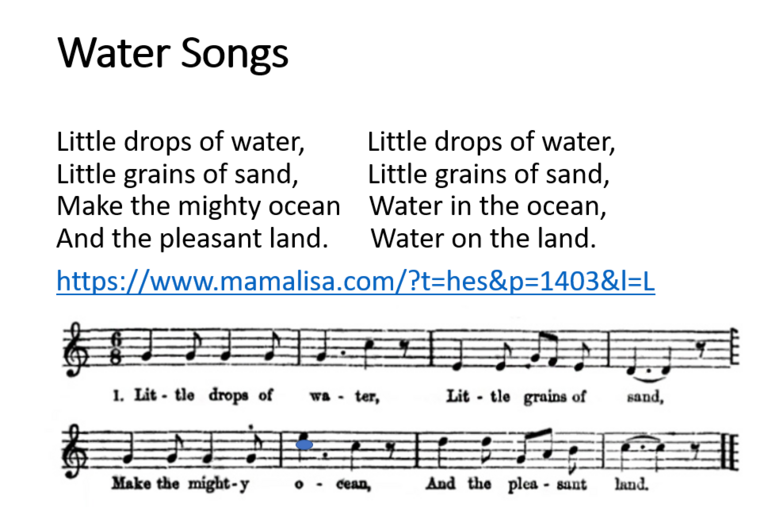

Initial activities about water include the presentation of words and phrases in combination with pictures, movement (Total Physical Response), songs, rhymes, chants, raps, poems, or stories dealing with the weather, nature, food, drinks, or hygiene. Children can draw, write, or create a weather report for the week using pictures and word cards, memorise nursery rhymes, or learn to sing songs about water and/or the weather. In the first two years, a basic vocabulary for topic areas around water and weather should be established (see basic water and weather words in the left margin).

Water_reflection_worksheet.pdf

pdf, 66 KB

From the abstract-conceptual to the analytical domain

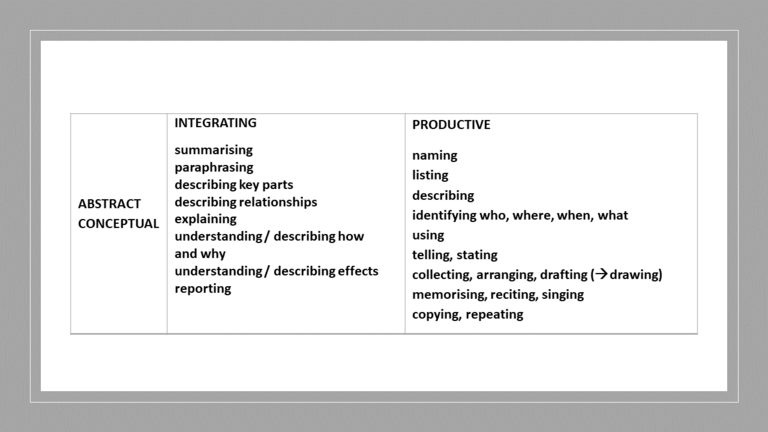

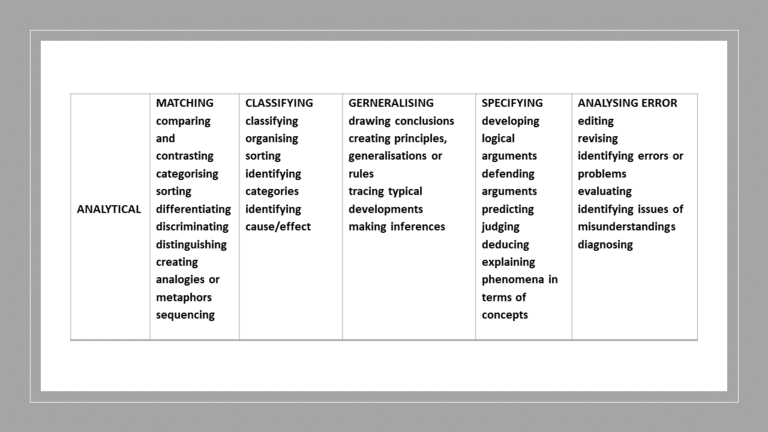

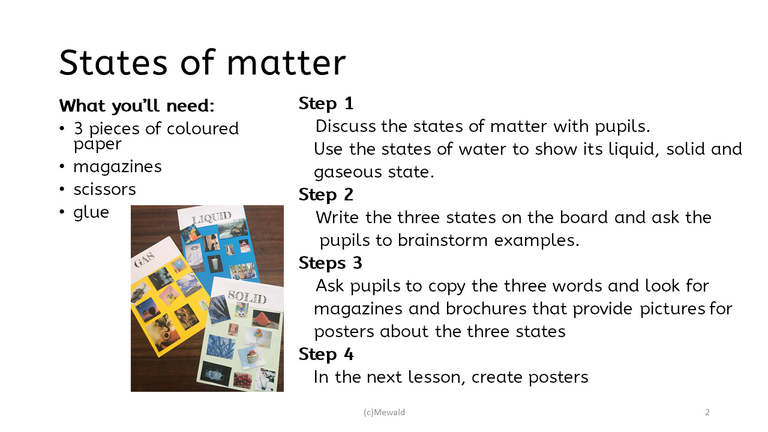

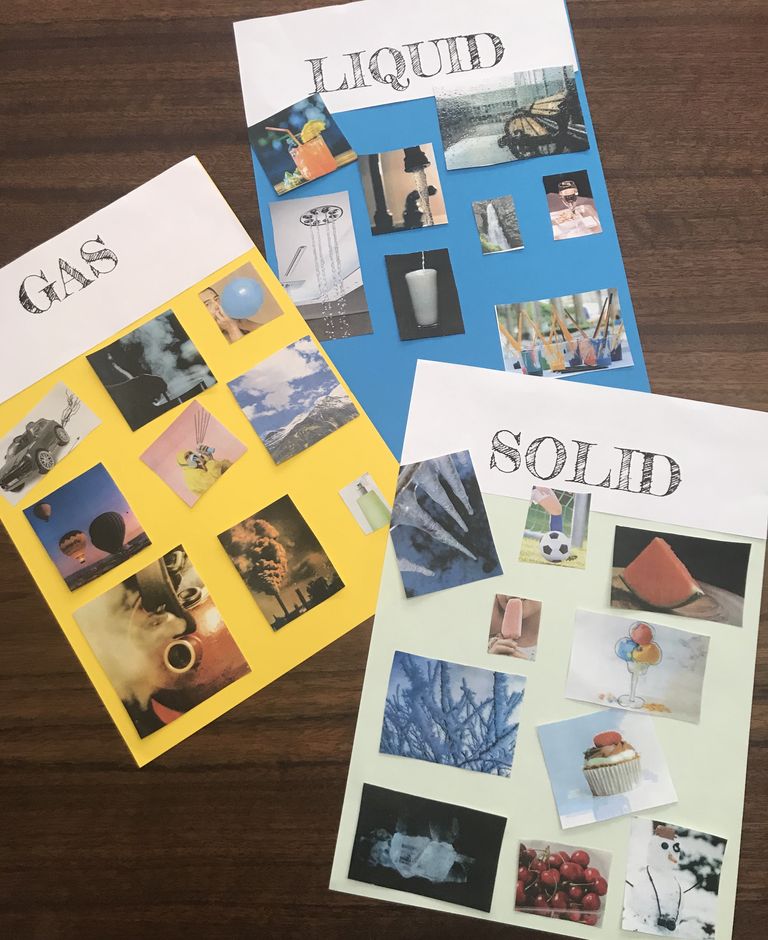

Working with picture cards and words, for example about the weather, creates abstract concepts and language used for integrating and symbolising (see Table 2). Children learn to match pictures and words — both abstract realisations of something real — with their experience of the same. Thinking in abstract concepts can mean to draw weather symbols, to record temperatures in weather charts, to measure the amount of water in containers and to create lab reports etc. When children link the colours blue and red on taps with the concept of cold and hot, when they measure wind speed, or read weather reports from symbols, their descriptive language develops towards a more abstract and conceptual understanding of their world, represented in models and symbols. First attempts to summarize stories through pictures, drawings, or text create insight into personal experiences with literature or basic scientific constructs. Children who experienced the various states of water and tried out using the words “liquid, solid, and gas” in real situations which gave them the opportunity to categorize various representations of those, will be able to hypothesize about the states of other materials they know. Analytical thinking (see Table 3) developed through comparing, contrasting, or categorizing all kinds of materials the children can name in their family language(s), the language of schooling, and probably a foreign language, will help children understand very abstract concepts like matter: see States of matter sorting activity in the left margin and the below picture.

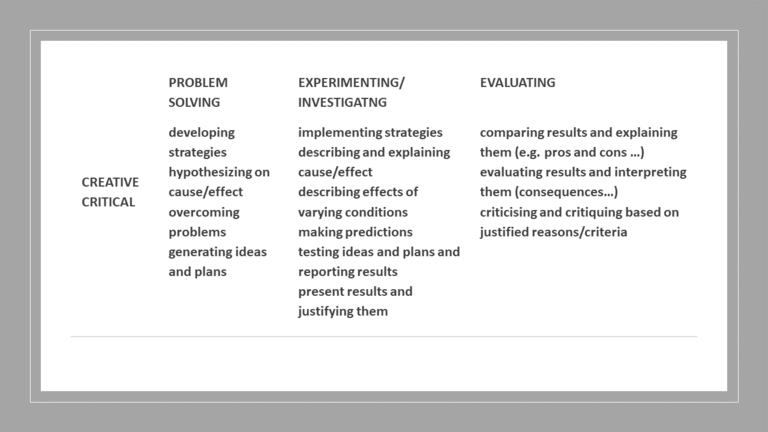

The creative-critical domain

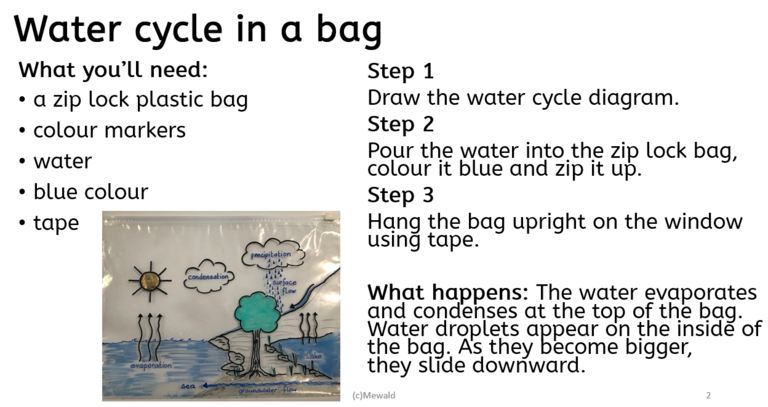

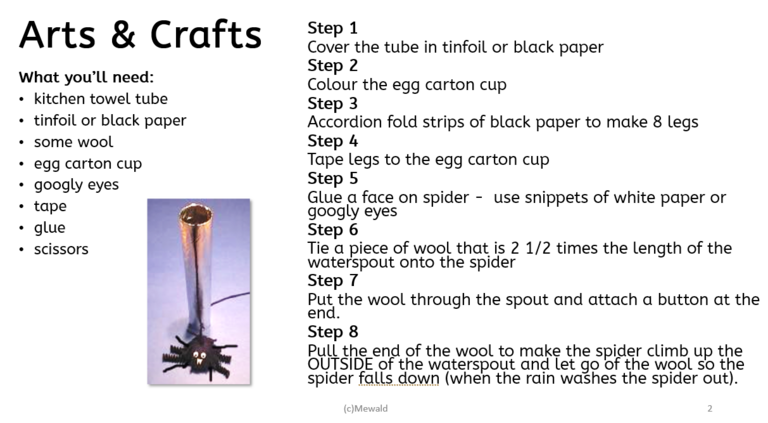

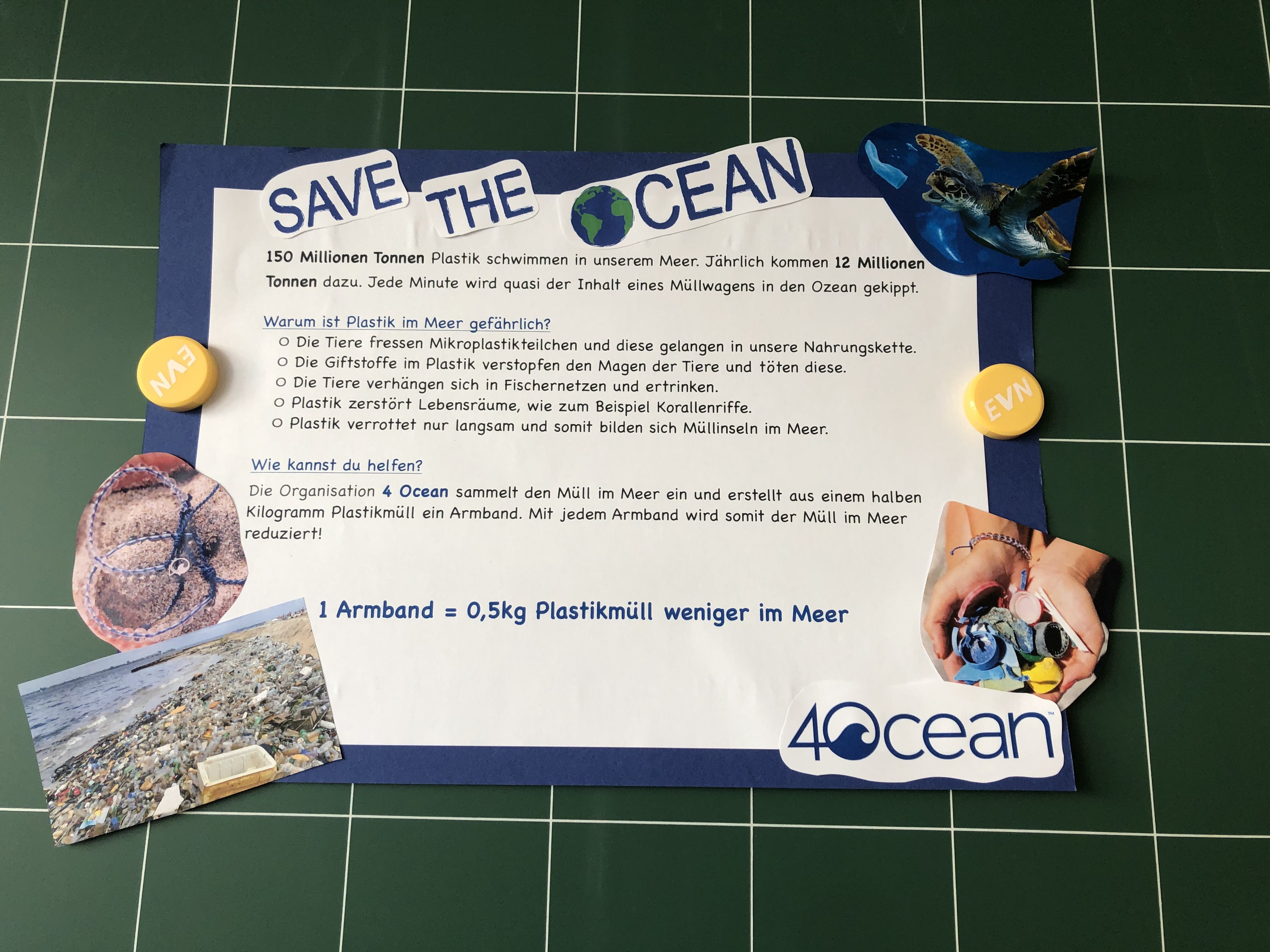

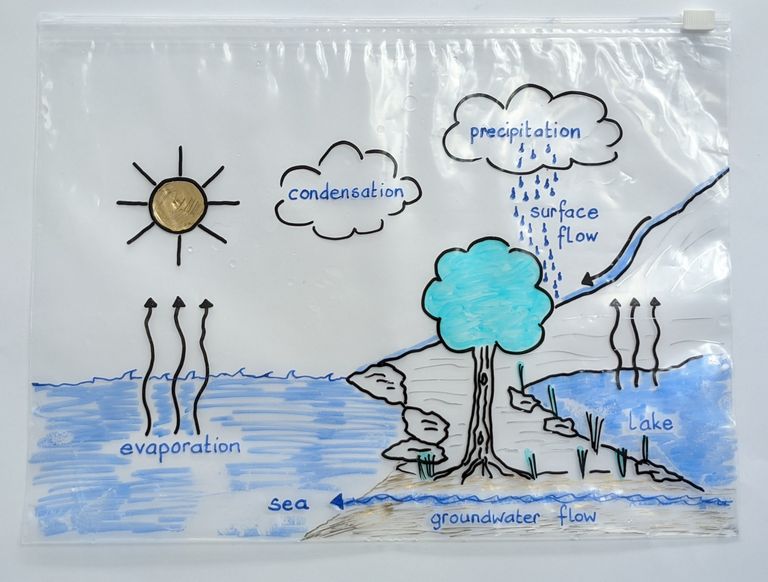

Through creative-critical thinking, children transfer newly gained content knowledge and language to critical analyses and the creative world (see Table 4). In doing so, they hypothesize about cause and effect, suggest solutions to problems they have identified, or they generate ideas how to find solutions to problems. After singing the song “The Incy Wincy Spider”, for example, children can allocate the physical processes of evaporation, condensation, and precipitation to the situations in the song. Using weather pictures or pictures in story books or reference books, children should also be able to speak about processes they experienced in similar and probably in extreme situations such as floods, gales, avalanches, mud slides etc. They can colour or draw the water cycle and analyse the processes depicted in the abstract representation with their own words, tell stories and discuss extreme weather they may have experienced or observed. This will guide them to an understanding of the term ecology in its biological sense: ecology in education. Critical discussions about sustainability can include reports about the children’s own water consumption or other children’s rights to water. Stories about countries where water is rare and must be used very responsibly, as well as stories about children who live in camps where neither drinking water nor hygienic facilities are available (see links in the left margin). Teaching about water should also spur learning about health and nutrition. Charts about the water content of foods (see left margin) are not only useful in the exploration of nutritional values. Additionally, they can initiate discussions about cultivating food, the concept of the water footprint, and the value of local food production as well as sustainability. Investigations at local farmers and supermarkets into the distances our food has travelled before arriving in the shelves should be followed by discussions of examples such as early potatoes from Egypt or sugar beets in Austria. Calculating distances and learning about countries and water situations where the food was produced provides material for cross-curricular learning and help children make the right decisions for their future in a healthy world. Creative solutions like the water play produced in the following project “save the ocean” suggest that even young child can reflect on ecological topics and find creative ways to express their thoughts about problems they have been made aware of.

ARGE

The following teaching & learning designs and materials were developed in the course "ARGE" by practising primary school teachers or teacher education students on a master's degree programme. Lesson Study or Action Research were implemented to validate processes and products.

CLIL Project: Save the Ocean

Projektplan von Lisa Foller

Save_the_Ocean_Lisa_Foller.pdf

pdf, 8 MB

Project report

This report gives insights into the classroom and how the teachers and pupils developed their project collaboratively.

pdf, 8 MB

CLIL Project: Gesunde Ernährung - Healthy Food

Wochenpläne von Blaga Zlousic

Mindfulness

Konzept zur Implementierung von Achtsamkeitsübungen im Englischunterricht von Diana Loiskandl

Mindfulness_im_Englischunterricht_.pdf

pdf, 487 KB

Buchstabenarbeit & CORONA Distance Study Mode

Checkliste und Linksammlung von Helene und Ulrich Strand

LeitfadenOnlineEnglischStrands.pdf

pdf, 116 KB